Research Highlights:

- Earlier blood transfusion after major surgery – when hemoglobin was below 10 g/dL rather than beow 7 g/dl - did not affect the risk of severe complications, such as death, heart attack, need for a heart procedure, kidney failure or stroke.

- However, the timing of the blood transfusion may be associated with a lower risk of irregular heartbeat and heart failure among people with heart disease, according to a new study of U.S. military veterans.

- Note: This trial is simultaneously published today as a full manuscript in the peer-reviewed scientific journal JAMA.

Embargoed until 3:57 p.m. CT/4:57 p.m. ET, Saturday, Nov. 8, 2025

NEW ORLEANS, LA - November 8, 2025 (NEWMEDIAWIRE) - An earlier blood transfusion- done when hemoglobin levels were higher - after major general or vascular surgery among people with heart disease was associated with a lower risk of some complications but not the most severe ones, according to a preliminary late-breaking science presentation today at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2025. The meeting, Nov. 7-10, in New Orleans, is a premier global exchange of the latest scientific advancements, research and evidence-based clinical practice updates in cardiovascular science.

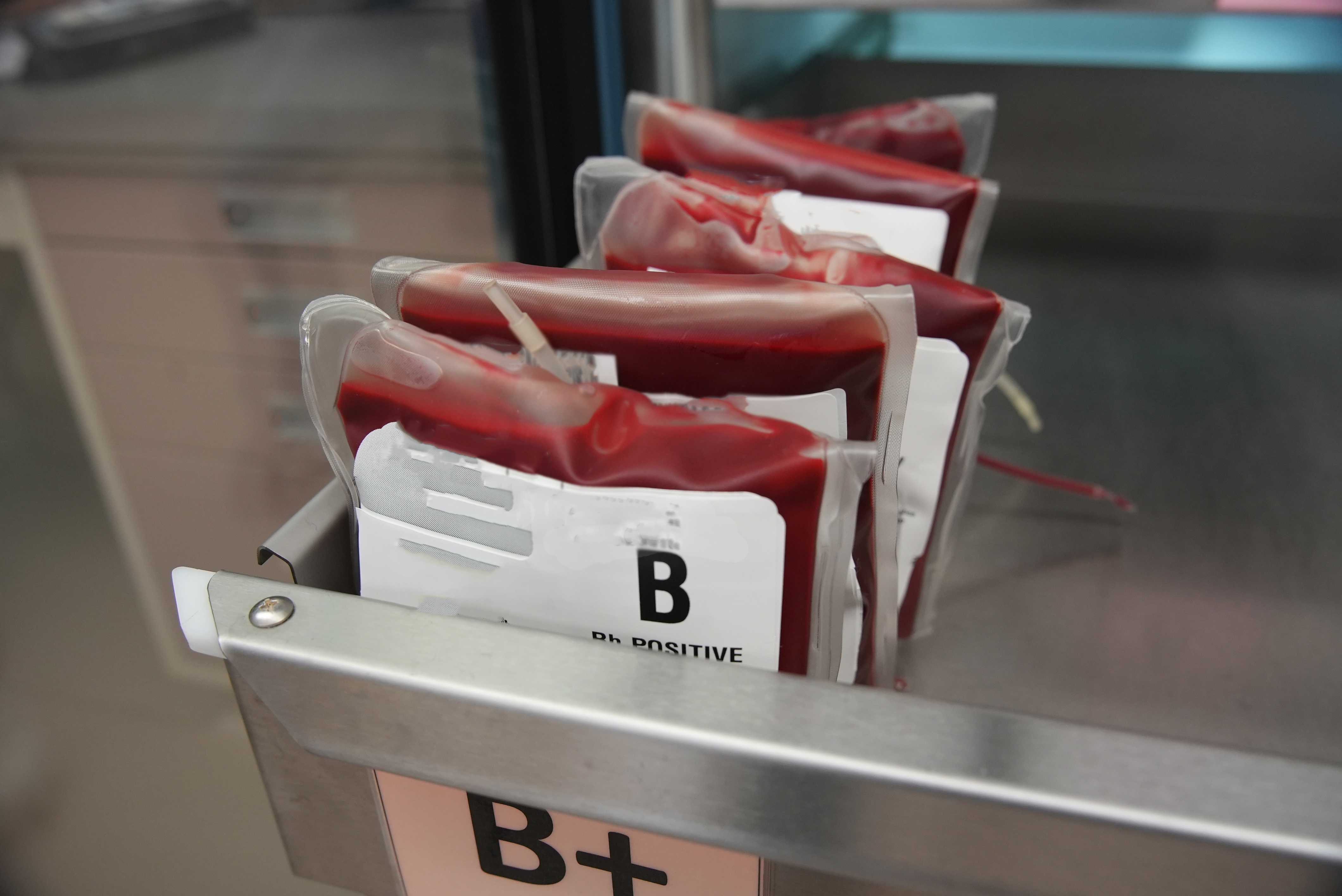

The Transfusion Trigger after Operations in High Cardiac Risk Patients (TOP) trial investigated whether transfusing blood earlier, when hemoglobin levels drop below 10 g/dL after major surgery, may prevent complications among heart patients better than a strategy that calls for transfusions when hemoglobin levels drop below 7 g/dL. Hemoglobin is a vital component of red blood cells that transports oxygen throughout the body.

In this study of more than 1,400 military veterans having major general or vascular surgery, hemoglobin levels were assessed after surgery and reassessed after each transfusion to determine if additional transfusions were warranted until discharge or 30 days, whichever came first.

The trial compared the combined frequency of major complications, such as death, heart attack, kidney failure, need for a heart procedure or stroke to less severe but still serious complications like pneumonia, sepsis, wound infections, new irregular heartbeat, cardiac arrest or heart failure, for the two strategies 90 days after surgery.

“When excessive blood loss or anemia occurs during or after surgery, a blood transfusion may be needed. For people with heart disease, the risk of complications due to the strain of blood loss means that the timing of a blood transfusion is critical,” explained lead author Panos Kougias, M.D., M.Sc., chair of the department of surgery at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, New York. “The current standard of care for most patients is to wait until hemoglobin levels are low before transfusing blood.”

“Our findings suggest that persistent blood loss in patients with serious underlying heart issues does not increase the risk of serious complications, such as death, heart attack, kidney failure, need for a heart procedure or stroke. However, it might place a greater strain on the heart than the volume from a transfusion, leading to problems like heart failure and irregular heartbeat,” Kougias said. “The earlier blood transfusion strategy may protect the heart from the effects of blood loss. It’s like keeping a car’s fuel tank above half full, while the transfusion-later strategy is like adding fuel only when the low-fuel light comes on.”

The analysis found:

- Severe complication rates - death, heart attack, kidney failure, need for a heart procedure or stroke - were similar among patients who received earlier or later blood transfusion: 9.1% in the early (liberal) transfusion group vs. 10.1% in the later (restrictive) transfusion group.

- Irregular heart rhythms and heart failure occurred in 5.9% of patients in the early (liberal) transfusion group compared to 9.9% in the later (restrictive) transfusion group, representing a substantial 41% lower risk among the early transfusion group.

“We were surprised that the restrictive transfusion strategy - giving less blood by only transfusing once patients’ hemoglobin levels were below 7 g/dL - was associated with a higher rate of heart failure,” Kougias said. “The traditional thinking has been that giving more blood may potentially overload the heart and worsen failure. Our finding suggests that in high-risk heart patients, persistent anemia might place a greater strain on the heart than the volume from a transfusion, leading to complications such as heart failure and arrhythmia. As this was a secondary outcome in our study, further research will be needed to confirm this finding.

“These results suggest that a one-size-fits-all transfusion strategy may not be best,” he said. “For some patients, waiting to transfuse remains safe and appropriate. However, for patients with serious underlying heart disease undergoing major surgery, our findings show that an earlier blood transfusion could help prevent serious heart complications, other than a heart attack.”

The study’s limitations include that most participants were men, so the results may not apply to women. In addition, health care professionals knew which patients received which transfusion strategy, which may have affected patient care. In addition, the number of severe complications was fewer than expected, which means that small differences may have gone undetected.

Study details, background and design:

- The TOP trial included 1,424 U.S. military veterans receiving care at 16 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers throughout the U.S., enrolled in the study between February 2018 to March 2023.

- Participants’ average age was 70 years old; 98% were men; and 75% self-reported they were white adults, 19% were Black adults and 4% were Hispanic or Latino adults.

- The criteria for the different transfusion strategies were hemoglobin below 10 g/dL for the early or liberal approach, and hemoglobin below 7 g/dL for the later or restrictive transfusion approach.

- Researchers measured hemoglobin levels after surgery and after each transfusion.

- Participants were followed for 90 days after surgery.

Co-authors and disclosures are listed in the abstract. This trial was funded by the Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development.

Statements and conclusions of studies that are presented at the American Heart Association’s scientific meetings are solely those of the study authors and do not necessarily reflect the Association’s policy or position. The Association makes no representation or guarantee as to their accuracy or reliability. Abstracts presented at the Association’s scientific meetings are not peer-reviewed, rather, they are curated by independent review panels and are considered based on the potential to add to the diversity of scientific issues and views discussed at the meeting. The findings are considered preliminary until published as a full manuscript in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

The Association receives more than 85% of its revenue from sources other than corporations. These sources include contributions from individuals, foundations and estates, as well as investment earnings and revenue from the sale of our educational materials. Corporations (including pharmaceutical, device manufacturers and other companies) also make donations to the Association. The Association has strict policies to prevent any donations from influencing its science content and policy positions. Overall financial information is available here.

Additional Resources:

- Multimedia is available on the right column of the release link.

- Link to abstract; and the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2025 Online Program Planner

- American Heart Association news release: Red blood cell transfusions may improve outcomes in heart attack patients with anemia (Nov. 2023)

- About Scientific Sessions 2025

- For more news at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2025, follow us on X @HeartNews, #AHA25

###

About the American Heart Association

The American Heart Association is a relentless force for a world of longer, healthier lives. Dedicated to ensuring equitable health in all communities, the organization has been a leading source of health information for more than one hundred years. Supported by more than 35 million volunteers globally, we fund groundbreaking research, advocate for the public’s health, and provide critical resources to save and improve lives affected by cardiovascular disease and stroke. By driving breakthroughs and implementing proven solutions in science, policy, and care, we work tirelessly to advance health and transform lives every day. Connect with us on heart.org, Facebook, X or by calling 1-800-AHA-USA1.

For Media Inquiries and American Heart Association Expert Perspective: 214-706-1173

American Heart Association Communications & Media Relations in Dallas: ahacommunications@heart.org

Bridgette McNeill: bridgette.mcneill@heart.org

For Public Inquiries: 1-800-AHA-USA1 (242-8721)

heart.org and stroke.org